Page 30 - Tạp chí bonsai cây cảnh BCI 2013Q4

P. 30

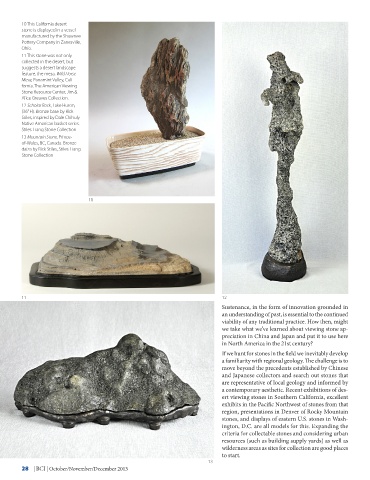

10 This California desert

stone is displayed in a vessel

manufactured by the Shawnee

Pottery Company in Zanesville,

Ohio.

11 This stone was not only

collected in the desert, but

suggests a desert landscape

feature, the mesa. Wild Horse

Mesa, Panamint Valley, Cali-

fornia. The American Viewing

Stone Resource Center, Jim &

Alice Greaves Collection.

12 Scholar Rock, Lake Huron,

(36” H). Bronze base by Rick

Stiles, inspired by Dale Chihuly

Native American basket series.

Stiles-Liang Stone Collection

13 Mountain Stone, Prince-

of-Wales, BC, Canada. Bronze

daiza by Rick Stiles, Stiles-Liang

Stone Collection

10

11 12

Sustenance, in the form of innovation grounded in

an understanding of past, is essential to the continued

viability of any traditional practice. How then, might

we take what we’ve learned about viewing stone ap-

preciation in China and Japan and put it to use here

in North America in the 21st century?

If we hunt for stones in the field we inevitably develop

a familiarity with regional geology. The challenge is to

move beyond the precedents established by Chinese

and Japanese collectors and search out stones that

are representative of local geology and informed by

a contemporary aesthetic. Recent exhibitions of des-

ert viewing stones in Southern California, excellent

exhibits in the Pacific Northwest of stones from that

region, presentations in Denver of Rocky Mountain

stones, and displays of eastern U.S. stones in Wash-

ington, D.C. are all models for this. Expanding the

criteria for collectable stones and considering urban

resources (such as building supply yards) as well as

wilderness areas as sites for collection are good places

to start.

13

28 | BCI | October/November/December 2013