Page 29 - Tạp chí bonsai cây cảnh BCI 2013Q4

P. 29

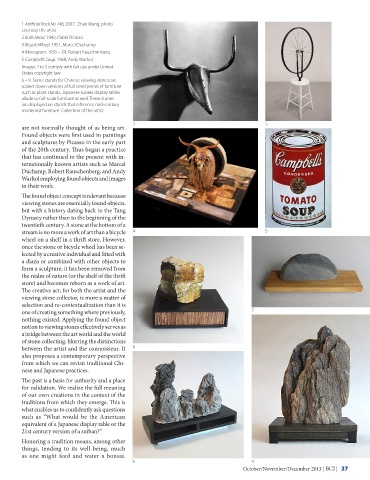

1 Artificial Rock No 148, 2007, Zhan Wang, photo

courtesy the artist

2 Bull’s Head, 1942, Pablo Picasso.

3 Bicycle Wheel, 1951, Marcel Duchamp

4 Monogram, 1955 – 59, Robert Rauschenberg.

5 Campbell’s Soup, 1968, Andy Warhol

Images 2 to 5 comply with fair use under United

States copyright law

6 – 9 Some stands for Chinese viewing stones are

scaled-down versions of full sized pieces of furniture

such as plant stands. Japanese suiseki display tables

allude to full-scale furniture as well. These stones

are displayed on stands that reference mid-century

modernist furniture. Collection of the artist.

are not normally thought of as being art. 2 3

Found objects were first used in paintings

and sculptures by Picasso in the early part

of the 20th century. Thus began a practice

that has continued to the present with in-

ternationally known artists such as Marcel

Duchamp, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy

Warhol employing found objects and images

in their work.

The found object concept is relevant because

viewing stones are essentially found objects,

but with a history dating back to the Tang

Dynasty rather than to the beginning of the

twentieth century. A stone at the bottom of a

stream is no more a work of art than a bicycle 4 5

wheel on a shelf in a thrift store. However,

once the stone or bicycle wheel has been se-

lected by a creative individual and fitted with

a diaza or combined with other objects to

form a sculpture, it has been removed from

the realm of nature (or the shelf of the thrift

store) and becomes reborn as a work of art.

The creative act, for both the artist and the

viewing stone collector, is more a matter of

selection and re-contextualization than it is

one of creating something where previously, 7

nothing existed. Applying the found object

notion to viewing stones effectively serves as

a bridge between the art world and the world

of stone collecting, blurring the distinctions

between the artist and the connoisseur. It 6

also proposes a contemporary perspective

from which we can revisit traditional Chi-

nese and Japanese practices.

The past is a basis for authority and a place

for validation. We realize the full meaning

of our own creations in the context of the

traditions from which they emerge. This is

what enables us to confidently ask questions

such as “What would be the American

equivalent of a Japanese display table or the

21st century version of a suiban?”

Honoring a tradition means, among other

things, tending to its well-being, much

as one might feed and water a bonsai.

8 9

October/November/December 2013 | BCI | 27